In June 1940, when the German armed forces were approaching Paris, the Parisians began to move out of the city, towards the south, where they believed they would be safe from the war. This exodus lasted for some people a few days or weeks, for others a few months, and some would never return to the city where they had lived. In Hanna Diamond’s book, we are told what this exodus meant for the persons involved, what their thoughts and feelings were, and about the military-political background.

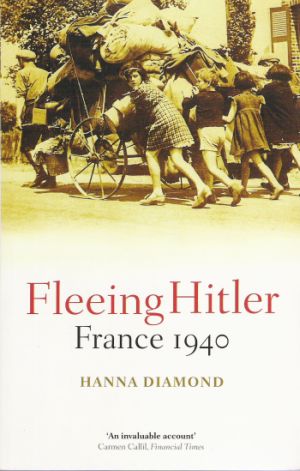

"Fleeing Hitler" -- front

—*—

The second world war (WWII) started in September 1939, when Germany and the Soviet Union attacked Poland. Britain and France declared war some days later, and these two countries were then at war with Germany. But on the western front, everything was quiet. It was called the “phoney war”, as no shots were fired, and everybody just waited. In May 1940, the German army advanced into Holland, Belgium and the Netherlands, and a real war had arrived in Western Europe.

The German forced advanced rapidly — the “Blitzkrieg” — and suddenly the people of Paris started to become worried. The French and British forces could not stop the Germans, and irresistibly the Germans moved toward the west — the Channel coast — and towards the south — threatening Paris.

The inhabitants of Paris had for some weeks seen refugees passing by, refugees from Holland and Belgium, fleeing towards the south. The Parisians were worried about what would happen. Then a few day into June 1940, the inhabitants started to flee toward the south. They made a hasty leave, and mostly had to resort to their own ideas about how to flee. Some made it by train, but an enormous number of persons started to leave by road, using cars, or bikes or on foot.

On June 22, armistice was made between Germany and the Vichy regime of France, and hostilities came to an end. The two weeks of fleeing came to an end, but for the refugees, the ordeal was not over. Some — the ones who were late to leave — managed to get back to Paris quickly. Others were stranded in the Unoccupied zone of France, and it took weeks or months to get back. And still other never returned. Either because they knew that returning to the Occupied part of France would place them in danger from persecution (Jews, refugees originally from Germany and other Central-European countries, foreigners that were just visiting France) or they decided that they had nothing to return to and preferred to stay in the south of France.

"Fleeing Hitler": Leaving Paris by train

The stories of the refugees have not been much explored. Diamond here gives us a good representation of what was on the minds of the refugees; before the exodus, during the exodus, and after. The sources used are written texts, like books published later and contemporary and later newspaper articles.

Main insights

The first insight gained is that the chaotic nature of this exodus was, to a large extent, the effect of lack of organised evacuation plans. There are several reasons for this lack, the main ones are

- no need for detailed plans — “our impregnable wall, the Maginot line, will stop the Germans, and they will never even see Paris at a distance”.

- no need for detailed plans, as even if the Germans entered the north of France, they would be stopped outside the gates of Paris — “we will stop them just like in WWI” (the battle of the Marne)

- planning for this eventuality sends the wrong message to the enemy — “we might not be able to defend Paris”.

- planning for this eventuality sends the wrong message to our citizens — “is our glorious Army incapable of defending the heart of France?”

The practical effect was that the citizens of Paris did not get a clear message about who should evacuate, and when. Certain categories were addressed specifically, like children, but for the grown-ups no clear directives were available. And the officials at the municipal, city and regional level did not provide any enlightening information.

"Fleeing Hitler": Leaving Paris by roads

This is why the evacuation was largely seen as an anarchic endeavour. People had to fend for themselves.

There was also the conflict — sometimes potential and sometimes real — of interference between the streams of refugees clogging the roads, and the army that needed to relocate in order to create some kind of meaningful opposition to the Germans. Sharing the same roads did cause logistical problems for all.

When the tide slowed to a stop, at the armistice, people could often be put up in local families or in hastily organized refugee centres. Some monetary contributions were handed out to the refugees, that they could use to acquire foods and other stuff necessary for life.

Some time after the armistice, repatriation started. Not all could be returned home. But many Parisians did return, and thanks to Paris being declared an “open city” before the Germans had come close to the suburbs, there had been no damage to the city in itself. So people could try to restore the kind of life they had had before evacuation. But life was not as good as before. Now they were exposed to food rationing, and not all workplaces could re-hire personnel.

Some numbers

In the beginning of July 1940, official estimates said that there were eight million refugees in France — 6.2 million internal French refugees; 1.8 million Belgians; 150,000 from Holland and Luxembourg. Of the 6+ million French, Parisians were about two million, and 800,000 were from Alsace-Lorraine

Blame

When people experience troubled times, they do not want to take on any responsibility for that. There must be somebody else that is the cause of these troubles. This is also what was noticed among the refugees.

Leon Werth was struck by the number of people he came across who needed to find someone to blame. ‘They shouted and cried expressions along the lines of “We have been sold out! We have been betrayed!” This popular accusation, that I have heard several times on the road, seemed to suffice in itself. I was never able to get a reply to the question “By whom?”‘ Those passing by in their expensive cars were assumed to be Jews. ‘The Jews sold us out!’ people cried. As refugees struggled, their anti-semitism grew. Such feelings laid the way for people to be sympathetic to Vichy’s later anti-Jewish statutes.

(Diamond, p 78)

That anti-Semitism could be noticed should not surprise us. In Germany anti-Semitism had been legally sanctioned for more than five years. In France there was a tradition of animosity towards the French Jews — cf. the Dreyfus affair. Having a lot of persons feeling desperate and on the run from their home, this provided an environment where latent anti-Semitism could become open anti-Semitism.

Did you notice the exodus?

Many persons have actually seen a glimpse of the exodus, or should we say a glimpse of a recreation of the evacuation of Paris. At the end of the well-known movie Casablanca (1942, directed by Michael Curtis; starring Humphrey Bogart, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid), we hear:

"Casablanca"

Bogart/Rick: If that plane leaves the ground and you’re not with him, you’ll regret it. Maybe not today. Maybe not tomorrow, but soon and for the rest of your life.

Bergman/Ilsa: But what about us?

Bogart/Rick: We’ll always have Paris.

Then we remember an earlier flashback scene, when these two have met in Paris and fallen in love. The Germans are approaching Paris. Bogart and Bergman were to escape together. Bogart waited vainly for Bergman at the railway station. Those scenes are from a timing point of view located at the peak of the exodus, when people were desperately trying to get out of the city, and succeeded, failed, or lost each other.

Even though the power of the movie Casablanca rests on what happens in the city of Casablanca, it can be enlightening to realize that the exodus from Paris was the setting for a critical part of the history preceding the main action in Morocco.

Peoples’ thoughts about Pétain

Maréchal Pétain was at the critical point in time entrusted with the governing of France. He, the hero of WWI, was now quickly taking steps to terminate hostilities between the French and the Germans. A cease-fire was agreed, and the French-German armistice was signed in Compiègne. Despite the fact that Pétain now was Head of State of a defeated France, he tried to recreate a national feeling of nationalism and “back to the roots” — in effect trying to eradicate modernism and return to a mindset of nationalism coupled with a devotion of the French soil.

In my family there is tremendous fervour for Marshal Pétain and I share these sentiments. His past, his prestige, and his age are all guarantees of his courage and the rectitude of his behaviour at the head of the French state which, without being aware of it, has just been substituted for the Republic- ‘Pétain’, my mother says,’is a father for France’ and this is just how he appears to us.

(Diamond, p 190)

Perhaps it was because the modern France had been defeated, and there were no other persons of the same stature as Pétain, that the Marshal had a surprisingly large and devoted following among the French.

Jean Monnet appears

In the history of the European Union, Jean Monnet has a special position as the originator of the idea of a European Union. He architected the first “trial version” of it, in the form of the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC).

Monnet is also mentioned here, as a strong supporter for the proposed Anglo-French Union of 1940 — an initiative that would prevent France from renouncing their promises to keep fighting alongside Britain. This union proposal was raised in the midst of the period that we are talking about here, but this proposal was quickly dropped, and France did ask for a separate armistice agreement with Germany.

But still, it is an intriguing thought that this Anglo-French union acted as a seed that would later grow up to be the ECSC, and a couple of decades later would result in the European Union.

Hanna Diamond

Hanna Diamond

The author

Hanna Diamond is Senior Lecturer in French History at the University of Bath. She lived and taught in Paris for many years and has spent her career researching the lives of the French people during the twentieth century.

(from publisher author presentation)

Conclusion

This was an interesting book, mainly because its topic has not been treated to this extent before. The reader gets a fair amount of political background, and of the main military actions taken. But the emphasis is on the people concerned — either as direct refugees themselves, or as French citizens in the south of France, citizens that did their best to host the refugees from Paris.

For obvious reasons, the main sources have been existing documentation in text, either printed or as manuscripts in the national archives. We would have preferred that this story had been treated forty years earlier, when lots of people were still alive, and had vivid memories of those weeks and months in 1940. Presumably we would have gotten a more diversified tapestry of experiences and opinions. Nevertheless, we have to acknowledge the the picture painted in this book seems like a solid account of those events and of the mindset of those times.

What is the relevance of this book? On the one hand it is another component in the story-telling of what happened during WWII, and in that respect a component with clear added value.

But we can also read this kind of book as a background when we try to understand what we see happening in our times. Even in Europe we have during the last thirty years seen refugees fleeing from their homes, and sometimes never to return. The kinds of thoughts that were in the minds of the Parisians in 1940 should to some extent correspond to thoughts in the heads of people fleeing from Srebrenica. There are lessons to learn from history, and we had better make good use of that kind of history, if we are to take some kind of control of our future.

Data

Hanna Diamond: “Fleeing Hitler — France 1940” (Oxford University Press, 2008) 255 pages, ISBN 13: 9780199532599 (book at openlibrary.org)

This page: https://whenthenightcomesfallingfromthesky.wordpress.com/2010/12/03/book-fleeing-hitler-france-1940-why-people-run-away-in-war/

I will add that my mother-in-law, a teacher at a Paris public school (Ecole Arago, Paris 14), was sent on evacuation with her school. I assumed she was talking about the summer of 1940. She had in tow her class of girls, 30 to 60, 9-year olds. They traveled the roads, hot and dusty, mostly on foot and slept in barns in the hay, contracting all sorts of pests. She told me of using harsh brushes on the little girls until they were bleeding to remove the pests that had burrowed under their skin. They were eventually told to return to Paris. She continued teaching in that school, retiring in 1954. I too am searching for more details and wished that I had written it all down as she recounted it. If any one knows where I can write for more information, please contact me.

I’m so pleased to find this book. I’m writing biography of my mother Francesca

and wanted to know where did my parent with their newborn baby, fleeing to from Jurzers, Versalles?

Hello Ollie,

Many thanks for putting up such a detailed account of the book. I am very pleased that you found it interesting.

You and your readers may also be interested in visiting my recently launched website:

http://www.fleeinghitler.org/

It came about because I needed somewhere to put all the family stories people were sending me as a result of reading the book.

Please do visit it and leave a comment.I’d be keen for anyone to send in their stories to us so we can build it as an online resource.

With best wishes

Hanna

I was interested to learn about your book. I am writing a memoir, mainly for my grand-children and have arrived at chapter 4, in which I describe what I do remember as a 6 year old child who was part of the column of regugees fleeing from Dieppe. I have in my possession frantic letters written between my mother, in France, and my father on a hospital ship in England during those 3 weeks following the 22nd May 1940

Dear Lily,

If you would like to post your story on our website:

http://www.fleeinghitler.org/

we would be very interested.

Best wishes

Hanna